Facial Harmony and Beauty: An Evidence-Based Guide

Back

Facial Averageness and Beauty: An Evidence Based Guide

November 13, 2025

Fundamentals of Beauty Series

TL;DR

Facial averageness is how closely a face resembles the majority of other faces within a population. Studies show that averaged (koinophilic) composite faces are usually rated more attractive than most real faces because averaging cancels asymmetries and pulls features toward typical, easy-to-process patterns. Facial averageness provides a reliable baseline for beauty, but top-tier attractiveness is achieved by adding specific, distinctive features.

Roadmap to Facial Aesthetics

This series covers six fundamentals of facial aesthetics: averageness, symmetry, sexual dimorphism, neoteny, proportionality, and adiposity. In this article we will discuss the science of averageness and koinophilia, considered to play a key role in perceptions of attractiveness across cultures and age groups. The map below shows how today’s topic connects to the other pillars at a glance.

The tenets of beauty.

Abstract

Facial averageness is defined by how closely a face matches the population mean in shape, size, and configuration, with non-average faces being more distinctive. Averageness plays a key role in facial aesthetics, and it is considered one of the six tenets of beauty. Decades of research show that composites created by averaging multiple faces are typically rated more attractive than their individual constituent faces. This preference for mean traits is known as koinophilia. An averaged (’koinophilic’) face is not to be confused with an ‘average-looking’ face on an attractiveness scale, as composites are perceived as more attractive than most real faces. Averageness is therefore a reliable cue of beauty. The most attractive faces, however, also have distinctive traits that make them stand out, meaning that increasing averageness only raises attractiveness to a point, after which additional features separate the attractive from the very attractive.

Faces range from atypical, unattractive configurations, through average features that are mildly attractive, to a distinctive aesthetic that is highly attractive.

QOVES Opinion on Averageness

The opinion we have at QOVES is that koinophilia (averageness) is an important aspect of facial aesthetics, which is rarely discussed and often misunderstood. Achieving more average features will certainly increase attractiveness, but only up to a point. Prototypical features are attractive, but very attractive faces go beyond averageness and possess distinctive qualities, often linked to the other tenets of beauty.

What is Facial Averageness and Distinctiveness?

In aesthetics research, the averageness of a face is defined by how closely it approximates the majority of other faces within a population. Rhodes1 describes an average face as one that has mathematically average trait values for a population. Averageness is also referred to as prototypicality, typicality, or normality. Distinctiveness is the opposite of averageness, meaning that faces that are high in averageness are low on distinctiveness.

The Averaged Face is Not Average (Koinophilia)

In everyday conversation, when people hear ‘average face’, they think of a 5/10 face on an attractiveness scale. In facial aesthetics research, averageness means something different: a composite image created by averaging many faces from the same demographic group (e.g., Japanese women). Preference and attraction towards average(d) or prototypical faces is known as koinophilia.

Averageness is

population specific

Researchers build separate averages by sex and ethnicity, because mixing groups changes the prototype being judged1.

The process of creating a composite of faces cancels or minimises extreme traits, small quirks, and asymmetries, resulting in a prototypical configuration of facial features that people usually find more attractive than most of the individual faces used in the process. To give a ballpark figure, people would likely rate an average(d) face as a 7/10, rather than a 5/10.

The average-looking face is different from an averaged (koinophilic) face

In this article, an ‘average face’ refers to a koinophilic, prototypical composite with average features, not a face with an average attractiveness rating. A clear example of this is these are these two composite (averaged) faces of an African American man and woman. It is very likely that you would rate both faces as above-average looking.

These images are created by “blending” multiple faces from a single population (in this case, African American men and African American women)

How is Averageness Attractive?

As we will explore in detail throughout this article, koinophilic faces are reliably found to be attractive across cultures and age groups. Decades of research highlight averageness as one of the key components of facial beauty and aesthetics, but how exactly is averageness attractive?

The process of averaging faces changes features in very specific and measurable ways, which impact attractiveness perceptions. By morphing or blending many individual examples from the same population, asymmetries cancel out, proportions rebalance, and facial features are “pulled” away from the extremes, resulting in a prototype that acts as the central representation of a category.

In his Theory of Forms, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato explained that the physical world is an imperfect expression of a higher, perfect, non-physical world2. In this non-physical world, things exist in their ideal form: there is a perfect apple, cat, house, and face.

Consider the two examples of apples below, which one do you prefer?

You probably chose the one on the left, and it is partly because it most closely resembles the ideal, perfect apple that exists in our minds. In this view, prototypes of categories may reflect the ideal exemplar that Plato discussed over two millennia ago, and that might help explain our preference for averageness.

Cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists today support this ancient idea (see ‘Perceptual Fluency’ theory). They argue that humans form mental prototypes for all categories based on all of the individual exemplars we come across, including human faces. Research shows that we respond favourably to prototypes, even from infancy3. This means that averaged, koinophilic faces that are closer to our mental prototype will be perceived as attractive.

Prototype Preference

Shows Up Early.

A study published in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology found that 5- and 9-year-olds preferred more average faces, showing an early developmental bias for prototypes.

Evolutionary biology provides another valuable perspective. Many morphological traits, including facial features, tend to function best at intermediate values rather than at the extremes. Natural selection, therefore, favours configurations at the mean level, something biologists call stabilising (or normalising) selection. From this angle, looking average or typical may reflect developmental stability, greater heterozygosity, and disease resistance.

Functionality also matters, as average traits can be the most functionally optimal; for example, a very small or very large nose would be less efficient than an average-sized nose. In short, humans may have evolved a psychological attraction to average traits because they can signal genetic quality and health. We explore this hypothesis and review the available evidence in depth in the section Why is Averageness Attractive?

Averaged faces from around the world

The Benefits of a Koinophilic Face

Averageness is not only linked to facial aesthetics; it can influence how others respond to your presence across various domains of life. Scientific research shows that attractive individuals can enjoy broad social and economic advantages. Below, we summarise well-documented effects associated with more koinophilic, attractive faces.

1. The Halo Effect (’What is Beautiful is Good’)

This effect was first described by American psychologist Edward Thorndike4, and it explains that a single positive attribute (like attractiveness) usually spills over into other judgments. Studies show that people with more typical and attractive faces are often rated as more intelligent, sociable, emotionally stable, responsible, and trustworthy5, 6. There is no objective or real relationship between beauty and all of these attributes, but people still attach them to more attractive individuals.

This is often referred to as the ‘What is Beautiful is Good’ phenomenon and can be understood as a cognitive bias for beauty, from which you benefit by improving facial aesthetics. The Halo Effect can impact real significant outcomes such as hiring, promotions, salary, and social inclusion.

It is important to note that increased averageness will only produce a modest Halo Effect. This is because although koinophillic faces are attractive, the most attractive individuals are not average, an idea we explore in detail in Very Attractive Faces Are Not Average. To reap the full benefits of the Halo Effect, you must take your face beyond average and achieve distinctively attractive features.

Do you see any similarities between actor Matt Damon and the average face of a white American man? There is clearly some resemblance, and both examples would be considered attractive by most.

Matt Damon, a conventionally attractive American actor, shares many features with the composite face of a white ahite American male

2. The Double-Devil Effect

This is the inverse of the Halo Effect. Atypicality or visible anomalies can, unfairly, trigger many negative trait attributions, making people seem less competent, warm, or moral7 This can amplify and worsen social penalties, for instance, exclusion or moral judgments. Women are particularly vulnerable to this effect, as unattractive women experience harsher penalties than men.

The name Double-Devil comes from the fact that negative aesthetic features trigger a “double” punishment or judgment. This negative cognitive bias can impact social relationships, professional development, and overall well-being.

An important point is that some of the most attractive faces include unique features that deviate from the population average. Deviation does not automatically trigger the double-devil effect, and standing out does not equal a penalty. Atypical or distinctive characteristics can push a face up or down on the attractiveness spectrum.

Unique features cluster at the extremes

For instance, gray coloured irises are a rare trait often seen as striking and attractive, whereas a pronounced occlusal cant (a visibly asymmetric smile) is an uncommon deviation that typically reduces attractiveness by breaking key facial reference lines (eyes, mid-nose, and mouth, see our Symmetry article).

Uncommon traits can be either attractive or unattractive

To understand why certain rare traits are compelling while others are not, you need to consider the 6 tenets of beauty in interaction.

3. The Purity Bias

Attractiveness is frequently (and mistakenly) associated with moral character. Evidence from moral psychology reveals that aesthetically pleasing faces are judged as purer and less capable of moral wrongdoing8. Put differently, people map traits of facial attractiveness like typicality or averageness onto intuitions about moral worth.

This linkage may result from an overlap in cognition around evaluations of physical appearance and character. A study on moral beauty by Klebl and colleagues8 found that people spontaneously perceive benevolence, honesty, and even “spiritual cleanliness” from attractive faces. This Purity Bias also leads observers to rate attractive individuals as less likely to commit moral violations.

4. The Health Signal

Facial averageness can also be perceived as a sign of health and genetic quality. Anthropologist Donald Symons9 argued that faces near the population mean performed better at tasks like chewing and breathing, and therefore averageness acts as a signal of good function. Thornhill and Gangestad10 instead suggested that average faces reflect greater heterozygosity, which is beneficial in the defence against parasites. Both perspectives claim that humans evolved a preference for facial averageness as one of many signals of biological fitness.

As we will see in more detail in Averageness and Health, averageness is perceived to be a signal of health, meaning that people perceive koinophilic faces as healthier11,12. However, the link between averageness and objective health measures is inconclusive12,13 and should not be taken as a reliable biomarker.

5. The Competence Premium

Koinophilic faces that are found attractive are rated as more competent and receive better job outcomes14, 15. Improving facial aesthetics via averageness, therefore, goes beyond looks and dating; it can also improve job, salary, and promotion outcomes.

This ‘competence premium’ is the Halo Effect with concrete consequences: higher leadership evaluations, stronger hiring prospects, and greater earnings16, 17. Studies show that the benefits are sex-asymmetric, with attractive women often receiving larger gains (and losses, too) based on their appearance17.

6. The Dating Dividend

Facial averageness can slightly improve romantic success as it increases perceived attractiveness and desirability as a mate. Experimental work across cultures and age groups shows that moving faces toward the mean (e.g., via composites) raises attractiveness and partner appeal for both men and women1, 18, 19.

The impact of this effect will, of course, heavily depend on where you currently stand on the attractiveness spectrum. As we’ve emphasised throughout this article, averageness can only take you so far.

7. The Confidence Loop

Believing one looks more attractive can shift behaviour in positive ways. This can be achieved by improving averageness, as we have seen it has a positive effect on facial aesthetics. Benefits from a more positive self-perception include an improved posture, a steadier gaze, and increased social approach.

This is consistent with the classic findings of Tesser in 1988, which showed that feeling attractive changes how people carry themselves20. The Confidence Loop reinforces itself: feeling attractive leads to more attractive behaviour, which elicits positive social feedback and strengthens self-esteem.

8. The Disgust Filter

Humans possess a behavioural immune system tuned to avoid potential disease cues21. Marked atypicalities or visible anomalies can trigger avoidance or disgust responses, irrespective of true disease risk21, 22. By contrast, greater averageness and typicality decrease these automatic aversive reactions by signalling “low risk.” Of note, this is part of a broader behavioural immune system that is sensitive to cues of disease or abnormality, not just facial atypicality.

The Disgust Filter describes how facial aesthetics can evoke a primal and automatic negative response in social interactions.

9. The Self-Esteem Multiplier

Enhancing koinophilic features and appearance can elevate self-esteem, which is a predictor of greater life satisfaction, resilience, and social confidence23. The Self-Esteem Multiplier highlights how improved facial aesthetics impact self-evaluations. This increase in self-esteem, in turn, is associated with a wide range of positive outcomes, including better mental health, improved resilience, stronger interpersonal relationships, and overall higher life satisfaction23–25.

The Self-Esteem Multiplier acts as a domino effect that starts with improved facial aesthetics

In short: Averageness and attraction span biology, psychology, and society, shaping how others judge us, how we judge ourselves, and opportunity. The science of beauty is also the science of advantage.

The science of beauty is also the science of advantage.

Why is Averageness Attractive?

Facial averageness, defined as closeness to the population mean in feature shape, size, and configuration, has been established to be a signal of attractiveness across studies and cultures. The fields of evolutionary biology and cognitive psychology provide two broad frameworks that explain why humans prefer facial averageness.

The ‘Good-Genes’ Theory

From an evolutionary view, attraction and perceptions of beauty are not random taste, but an adaptation that guides our choices toward higher-value mates to achieve successful reproduction1. In simple terms, humans evolved to like individuals with good genes capable of producing healthy offspring. In this sense, averageness is proposed to signal developmental stability or the ability to withstand disease, toxins, and other stressors during growth. Some authors have also linked average traits to heterozygosity (genetic diversity), which could improve immune defence1, 12, 18.

The highly influential anthropologist Donald Symons9 instead argued that averageness was related to function. He stated that in continuously distributed traits, intermediate (average) values are more efficient. For example, Symons explained that an average-sized nose would be more efficient for breathing than an extremely small or extremely large nose.

“Beauty is in the adaptations of the beholder” - Donald Symons

Cover of Donald Symon's influential book, The Evolution of Human Sexuality

Some biologists and pathologists extend on this evolutionary view and propose that averageness (and symmetry) correlate with parasite resistance. If this were the case, then preferences for typical faces would have reduced the risk of choosing more vulnerable partners12, 18.

Evidence and limits

It appears that humans evolved to see averageness as a signal of health, as studies show that people perceive average faces as healthier1, 12. It is also the case that marked deviations from averageness (and symmetry) do co-occur with certain chromosomal or clinical conditions26, 27. However, the evidence for an objective health link is inconclusive, with a very recent meta-analysis finding no clear link between averageness and health measures13.

Speculative note. One plausible explanation for the inconsistency is the result of old wiring in a new world. In the past, facial averageness may have correlated more strongly with health or genetic quality. Today, advances in medicine, nutrition, and hygiene may have weakened those links, while our preference for prototypical faces persists. This, of course, is all speculative, and a better explanation concerns our brain processing systems.

Average women from around the world.

The ‘Processing Fluency’ Hypothesis

Cognitive theories explain that our preference for averageness is due to a bias for prototypicality and how we process visual stimuli. This is related to the processing and recognition systems in our brain and how we come to form mental prototypes of categories. As humans, we form mental prototypes for different categories by averaging encountered examples. Prototypes are easier to process and require less mental effort, which, in the case of faces, translates into higher attractiveness ratings28. By definition, a koinophilic or averaged face resembles our mental prototype very closely, and we respond favourably to those mental models.

Evidence from cognitive neuroscience agrees with this: faces approximating the population average are recognised more quickly and elicit smaller neural responses, implying greater encoding efficiency29. In simple terms, koinophilic faces are not only processed faster, but they literally require less brain ‘power’.

Average Faces are Processed Differently in the Brain

According to this cognitive explanation, processing fluency is what underlies perceptions of attractiveness. In summary, this theory states that human cognition favours mental prototypes, which are defined as the average of individual examples of specific categories. The perceptual fluency account also states that mental prototypes are not fixed or innate; cultural exposure and perceptual adaptation update our mental models continuously. This makes sense: if prototypes or exemplars are formed by averaging all of the individual examples of a category, exposure to those examples will shape our prototypes.

Fast in the brain. Neuroscience shows that the early face-response signal (N170) is faster and smaller for averaged and highly attractive faces than for low-attractive faces, suggesting easier processing29.

This is supported by a number of studies. In one, members of an isolated hunter-gatherer tribe were shown averaged European faces and averaged faces from their own group. They showed a preference only for average faces of their own community, likely because they didn’t have a mental prototype for “European faces”30. Findings from developmental psychology show that adults prefer average faces more than 9-year-olds, who in turn prefer them more than 5-year-olds, consistent with a refinement of an average prototype as children are exposed to more faces3.

Nuances of Averageness

Very Attractive Faces Are Not Average

In a landmark paper, Ghillian Rhodes1 concluded that although average faces are attractive, that does not mean that all attractive faces are average or that average faces are optimally attractive. In other words, averageness can only take a face so far up the attractiveness ratings, and non-average faces can also be attractive. This key point must always be acknowledged when considering the science of averageness and beauty.

Title page of the seminal paper by Alley and Cunningham in the journal Psychological Science.

Years before Rhodes, research psychologists Alley and Cunningham published a widely cited article titled “Average Faces Are Attractive, But Very Attractive Faces Are Not Average”. In their paper, they support the idea that averaged, koinophilic faces are attractive, but add nuance by claiming that very attractive faces are distinctive (non-average).

Composite of 60 white female faces (a) and the composite of the 15 faces from the set that were rated as most attractive (b). Morphs adapted from Apicella et al. (2007)

Their claims do have important theoretical support. Going back to Why is Averageness Attractive?, evolutionary theory states that intermediate trait values are favoured, but it is also true that evolution often favours traits that deviate from the mean. For instance, in species like the peafowl bird or the long-tailed widowbird, female choice drives directional sexual selection: extravagant, extreme tails win more mates even when they are costly in other domains (like flying or fighting).

The peafowl bird and long-tailed widowbird are examples of female mate selection of extreme traits.

Alley and Cunningham31 argue that something similar occurs in humans. Males favour atypical cues of youth and fertility in females, for example. This means that women in their reproductive age will be preferred over those with a mean age. This links back to the idea of youthfulness or neoteny, another tenet of beauty which plays a fundamental role in facial aesthetics. An example in humans is male height, as women consistently find above-average height more attractive.

The most desired traits, sometimes fall outside the mean

Empirical evidence also supports the idea that many attractive features actually lie away from the mean. For instance, Cunningham and colleagues32 found that prominent cheekbones and a large chin were attractive male characteristics, and work in orthodontics shows that very attractive women have some protrusive (not average) dentofacial pattern33.

DeBruine and colleagues 34 took a step further by directly testing whether facial attractiveness is mostly a result of facial averageness. The authors manipulated faces to make them less koinophilic but more attractive, therefore examining if attractiveness could really be separated from averageness. The graph below summarises the results from their work, and it perfectly captures the fact that averageness is reliably correlated with attractiveness, but the most attractive faces actually deviate from average features.

Studies showed that the most attractive faces were not the ones with the most typical features

The results of five different experiments conclusively showed that there are specific non-average facial features that are found attractive. In simple terms, some distinctive features can take a face away from average while still increasing attractiveness.

Averageness Across Cultures

There is strong cross-cultural evidence that facial averageness is associated with attractiveness. Preferences for koinophilic (prototypical) faces are found in Western and non-Western samples, consistent with evolutionary and cognitive explanations rather than purely cultural accounts. The research reviewed below indicates that, contrary to popular belief, beauty is often not in the eye of the beholder.

A study by Rhodes and co-authors11 revealed that increasing averageness enhanced attractiveness ratings for both Chinese and Japanese faces, as judged by participants from those same countries (facial symmetry had a similar effect). In a more recent 2019 study, participants from India, Cameroon, Namibia, and several European countries rated Czech faces closer to the average as more attractive, although the strength of this effect varied by cultural and socioeconomic context35. Similar work found that across Czech Europeans, Czech Vietnamese, and Asian Vietnamese, facial averageness was positively correlated with perceived attractiveness36.

Perhaps the most fascinating study on this topic comes from a cross-cultural study by Apicella and colleagues30 published in the journal Perception. The authors studied preferences for averageness in both a European sample and in an isolated hunter-gatherer population, the Hadza in Northern Tanzania in Africa.

More average = more attractive? The top row (a) shows 5-face composites and the bottom row (b) shows 20-face composites, which ones do you find more attractive?

Adapted from Apicella et al. (2007), Perception.

Results from the study showed that across these two very different cultures, people generally preferred more average or koinophilic faces. However, the Hadza showed no preference for averageness in European faces. This may be because the Hadza have limited visual experience of European faces, meaning they likely don’t have a mental prototype for that demographic. These findings are important because they support the idea that although preference for averageness is universal, exposure and visual experience play a critical role, consistent with the Processing Fluency hypothesis.

Averageness and Health

Koinophilic (averaged) faces likely signal an absence of disease and not extra fitness or health. In simple terms, it is not that average faces signal extra health, but that faces at the extremes with strong deviations from the mean could be associated with clinical conditions. Physicians have noted that large departures from typical facial structure are more common among individuals with certain chromosomal or developmental disorders26, 27, which is why extreme non-averageness can read as a health red flag. Some longitudinal evidence (that tracks participants across time) found that 17-year-olds with more average faces tended to have better childhood health histories1, 37. Rhodes and colleagues11concluded that facial distinctiveness had a small correlation with poor childhood health in males and poor current and adolescent health in females. However, this study is limited by a sample of 17-year-olds only. Zebrowitz and Rhodes38 best summarised the pattern by stating that the link is driven by below-the-median cases. Put simply, drifting far from the population prototype can hint at worse health, but moving around the centre does not add health points. After crossing the “typical developmentally stable” bar, more averageness won’t signal more health.

Sturge-Weber Syndrome produces visible facial atypicalities and carries real clinical risks. Source: https://obgynkey.com/vascular-anomalies-3/

A 2025 scoping review by Obrochta and colleagues analysed21 studies on facial features and health13. Regarding averageness specifically, the authors conclude that the link is weak and mixed: some studies have associated koinophilic faces with increased heterozygosity39, lower oxidative stress40, and the number of children41. On the other hand, larger studies found no link between averageness and heterozygosity, no association with infectious illnesses or antibody levels42. Overall, the evidence is inconclusive, and more research is needed.

Averageness and Symmetry

As previously discussed, averageness and symmetry are intertwined, and both predict attractiveness18. By necessity, averaging a face cancels random left-right asymmetries, producing a more symmetric prototype that is also an averaged face. In other words, averaging naturally produces symmetry, which explains why both cues are closely related and why both of them predict perceived beauty and attractiveness.

It is thought that symmetry is largely a by-product of averageness, contributing to perceptions of attractiveness by shaping perceptions of normality (see diagram below). When averageness is statistically controlled, the independent effect of symmetry on attractiveness shrinks significantly43, 44. That pattern suggests symmetry often boosts attractiveness because it makes a face look more prototypical, not because symmetry acts entirely on its own.

But the relationship between averageness and symmetry can get more complex once we consider other variables. As we have repeated throughout this article, highly attractive faces are not copies of the mean: they often deviate from the prototype along dimensions like sexual dimorphism or neoteny while retaining bilateral facial symmetry.

The Science of Facial Averageness

The study of facial averageness in the context of aesthetics and beauty started with the work of Langlois and Roggman in 1990, which they provocatively titled ‘Attractive Faces are Only Average’. Because at the time of their research, evidence showed that attractiveness ratings were very consistent across raters in different cultures and age groups, the authors set out to define and explain the features of beauty that were universally liked. Inspired by the evolutionary and cognitive perspectives we have described in this paper, Langlois and Roggman decided to test empirically how averaging facial traits impacted perceptions of attractiveness.

Studies showed that composite faces creates using more individual faces were rated as more attractive

How is Averageness Measured?

Experimental Manipulations

In their landmark study, Langlois and Roggman28 created computer-generated face composites. They digitised each photo, lined up all faces to the same size and position by matching the pupils and midpoint of the lips, and then created composites by mathematically averaging the corresponding pixels across faces. In short, they blended many individual faces into a single koinophilic prototype.

Construction of an average face: multiple individual faces are warped to a common mean shape, then their pixel values are averaged to produce a single composite identity.

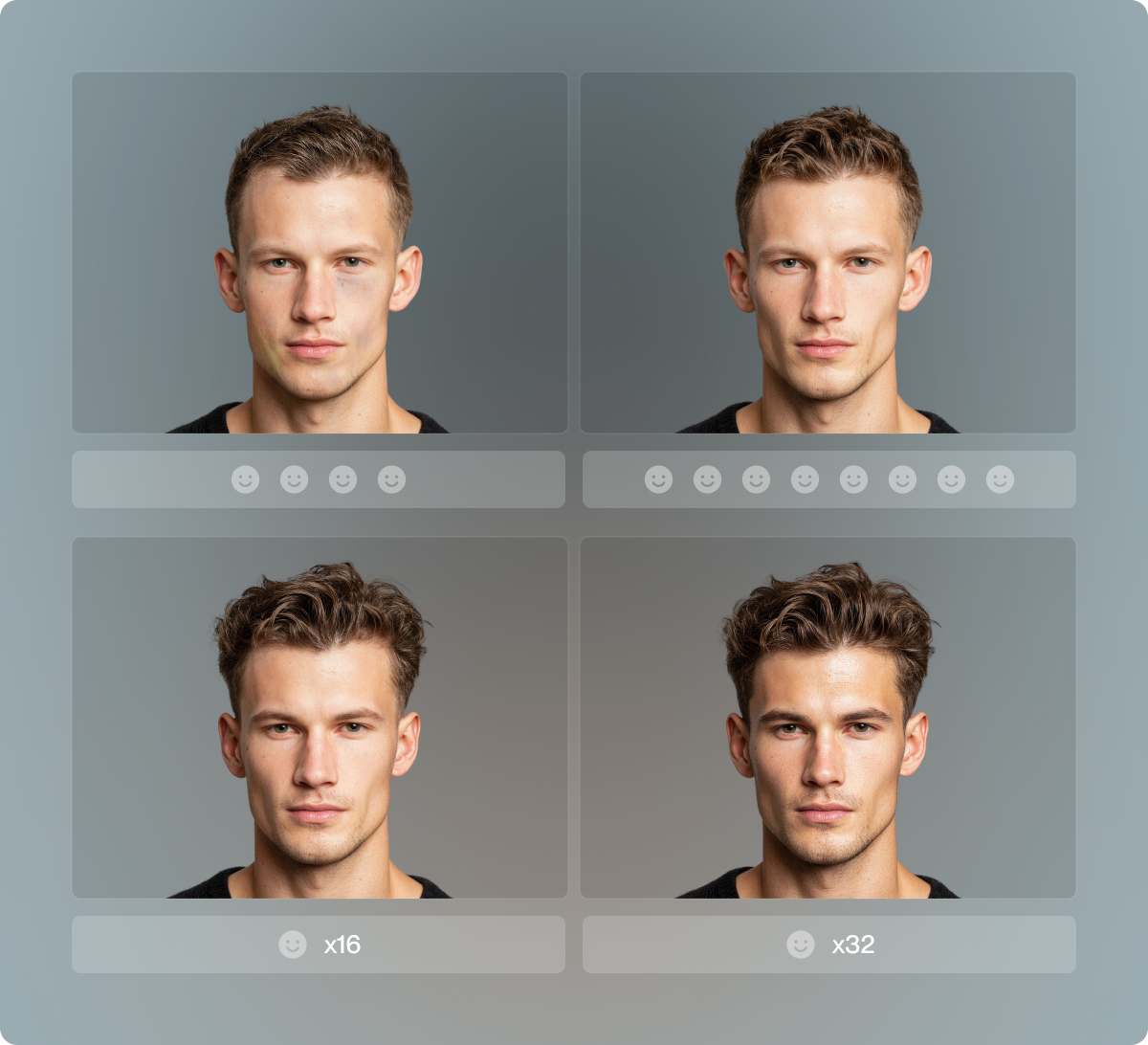

The authors didn’t simply compare composites to single faces; instead, they created five levels of averaging: 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 faces. This allowed them to test directly how increasing averageness affected attractiveness.

Critics quickly appeared and pointed out flaws in the method of Langlois and Roggman. Some argued that the average(d) faces they created actually had non-average features like large eyes and lips, and smooth complexions as a result of their computer manipulations. Others stated that averaged faces were found attractive mostly because they were symmetrical (as fluctuating asymmetries were reduced). However, despite criticisms, the effect of averageness on attractiveness remained robust as science progressed and improved its methods.

Later studies placed landmarks along feature outlines and used shape alignment, separating shape from texture. This addressed the early issues of large eyes and lips, and smoother skin. An elegant study by Valentine et al.45 tested averageness using only side-profile images, eliminating bilateral symmetry cues. Likewise, Rhodes and colleagues46 statistically controlled for symmetry. Using different, and more advanced methods, the result was consistent: averageness reliably increased attractiveness.

Inspired by Valentine et al. (2004) study design in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

Not just symmetry. When researchers use only side profiles, which remove symmetry cues, more average profiles are still judged more attractive45.

Natural Faces

The other methodology used by researchers to assess koinophilic faces and beauty is the use of natural, unedited faces with varying degrees of ‘averageness’. Because it is possible to estimate the average face of a given population, it is also possible to determine how closely any individual face resembles the population mean. This allows scientists to examine how typicality relates to attractiveness in a way that most closely resembles real-world conditions, since faces are not manipulated. In psychological research, this is called ‘ecological validity’, and it refers to how well the results of a study can be generalised to the real world. An important limitation is that these types of studies can only establish a correlation, but not causation.

Results and Findings

More Faces Increase Koinophilia and Attractiveness

The classic composites of 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 faces created by Langlois and Roggman28 showed that attractiveness ratings rise with the number of faces averaged. Composites made from 16 and 32 faces were rated significantly more attractive than their corresponding individual faces; smaller composites had no effect. This effect was observed in both men and women.

A koiniphilic face is more attractive than most. A 1990 study by Langlois and Roggman found that only ~20% of individual faces were rated as more attractive than an averaged koinophilic face.

Caricaturing Away From the Mean

Researchers have also examined what happens when you exaggerate or ‘caricature’ the difference between an individual face and the average configuration for its corresponding population. In simple terms, this involves manipulating a face by taking it further away from the mean. Rhodes and Tremewan47 tested this and found that the attractiveness of faces can be reduced by moving facial features away from the average. However, recall that there are specific non-average characteristics that make a face more attractive (see Nuances).

Before

After

Drag the slider to see how researchers 'caricature' faces away from mean values (average features)

Independent Effect of Averageness

Averaging increases bilateral symmetry and smooth texture, but later studies controlled those confounds and still observed an independent effect of averageness on attractiveness. Landmark-based shape alignment removed the effect of texture and colour, and profile-only designs removed symmetry cues altogether. In both cases, the preference for averageness persisted45, 46, 48.

Natural (unmanipulated) Faces

Across correlational work with real, unedited faces, faces closer to the average are generally judged more attractive than distinctive faces, replicating across multiple datasets and measures1, 45, 46, 48.

A very recent (2025) study by Lee and colleagues44 directly measured averageness, symmetry, and sexual dimorphism from photographs of real faces and found that facial averageness significantly predicts attractiveness in both male and female faces, independent of other factors. This work stands out for its ecological validity, as it used unmanipulated images and robust statistical modelling to isolate the effect of averageness.

Nevertheless, specific distinctive features linked to neoteny and sexual dimorphism are consistently linked to the most attractive faces.

Why Averageness Does Not Determine Attractiveness: Limitations

As we have reiterated throughout this article, averageness interacts with other important cues (symmetry, proportionality, skin quality) and with exposure/adaptation, which can recalibrate one’s internal “average”1, 12, 49. While average(d) faces are attractive, very attractive faces are non-average in specific ways often tied to sexual dimorphism and neoteny, such distinctive features can raise appeal beyond the prototype31, 34.

Conclusion

The scientific literature shows a robust and significant effect of koinophilic faces (averageness) on perceived attractiveness. Decades of experimental studies show a causal effect across methodologies and cultures, demonstrating a universal preference for averageness or typicality. Koinophilic faces, although attractive, are not the most attractive. Research shows that very attractive faces have specific, distinctive features defined as non-average. Evolutionary biology and cognitive psychology provide complementary accounts for this bias for averageness, although the link between objective health and koinophilic faces is inconclusive. In practice, moving towards an average configuration of facial features will improve attractiveness, but only up to a certain point.

References

- 27

Hoyme, H. E. Minor anomalies: diagnostic clues to aberrant human morphogenesis. in Developmental Instability: Its Origins and Evolutionary Implications: Proceedings of the International Conference on Developmental Instability: Its Origins and Evolutionary Implications, Tempe, Arizona, 14–15 June 1993 (ed. Markow, T. A.) 309–317 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1994). doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0830-0_24.